If week one of the discursive screening What We Talk About When We Talk About History at TPW R&D, was about translating history, then week two was about transmitting history.

Trans·mit [trans-mit, tranz-] verb.

trans·mit·ted, trans·mit·ting. verb (used with object)

1. to send across

2. to communicate, as information or news

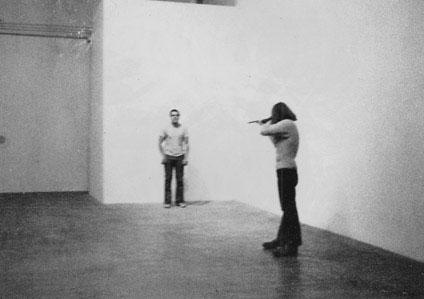

Three videos screened on March 20: Queen Mother Moore speaks at Green Haven Federal Prison by People’s Communication Network (1973), Four More Years by TVTV (1972), and Shoot by Chris Burden (1971). In a shift from the translation of history into the transmission of it, I am curious about the act of ‘looking’ and its connection to structures of power. Employing the term transmission here, I am referring to the works themselves and the conversation subsequent to the screening.

Each of the above videos attests to the power of the camera, or the power of the portapak to be precise. In an era that saw the emergence of portable camera technology, when people were less reticent when speaking to the camera, there was a ‘grace period’ that occurred – where the power of the camera and therefore the power of looking reigned supreme.

Different modes of “infiltration” by the camera resonated in all three videos. Whether through an infiltration into the prison, the ’72 Republican National Convention or Burden’s performance piece, the artist and the viewer acted as witness and spectator to the transmission of history. The bodies of the camera operators are themselves representative of modes of access, connecting to race in the United States in the 1970s through the interplay between the racial body and movement through and across space, and linking back to power in the documenting of historical acts.

“In Shoot, I’m shot in the upper left hand arm by a friend of mine with a 22 rifle. The only thing I have is a film clip about 8 seconds long. So I’m going to begin by saying it was me doing the actual performance. Some of the things to listen for are “do you know where you’re going to stand”, then later right before the film clip happens you’ll hear me say “are you ready?” and then you’ll hear the clicking of the super8 camera. Later when the shooting is over, another thing to listen for are the empty shell droppings on the concrete floor.”

This quote is an excerpt from Burden’s introduction to his video. Through his voice over, Burden guides us through the documentation of his performance, structuring the frame of viewing for his audience, and foreclosing alternative readings of his piece. Burden’s exercise of power and control is evident throughout. Control of the gun, control of the performance, control of the ways in which we look, hear and experience.

Employing the repetitive terms commonplace to systemic modes of power – white, American, male, artist, Burden – the performance artist – chooses to enact violence onto his body. In direct contrast, the voices in Green Haven prison scream unrelenting re-actions against the violences of history. Against the violations enacted upon the bodies of those who aren’t white, male, artists in Queen Mother Moore Speaks… the juxtaposition of Burden’s performance leaves us feeling the striking contrast of racial privilege in history’s transmission.

The irony of repetition, that we tire of the same story but keep replicating the same narratives, means that we cannot omit thinking about race, power, privilege, access and sight in our dialogues with work like Queen Mother Moore Speaks at Green Haven Prison. So I return to it, in all its manifestations, I return to our conversations on race, representation and power. Again, and again, and again.