Montreal-based writer and curator Vincent Bonin responds to Tris Vonna-Michell’s exhibition, Capitol Complex, at Gallery TPW.

Tris Vonna-Michell is known for performances in which he brings together dense bundles of phrases to abridge a historical narrative that would otherwise be deployed through longer duration. Words are uttered in a rapid syncopated pace and repeated within a brief time frame like anchoring points. Vonna-Michell’s slide-based installations do not document his performances, but rather recalibrate a photographic archival aftermath on which he superimposes other disjointed stories. His practice manifests itself through a format that is both recursive and prospective. New work thus often develops from reconfigurations of past work, until the accumulated differences guide him towards another direction. His acute perception of contingency allows for possibilities outside of the logic of project-based work, a logic which now seems to prevail as the dominant production mode in contemporary art, where an artist has to plan everything ahead, and offer something new (and to also renew himself) each time he is invited to exhibit. The piece that best demonstrates Vonna-Michell’s methodology is Finding Chopin, a performance and installation series begun in 2005 and ongoing.1 The idea for it was triggered after a conversation between Vonna-Michell and his father about the reason why his family moved to Southend-on-Sea, in Essex, England. Vonna-Michell’s father suggested he find and ask Henri Chopin, a concrete poet: “all you need to know is that he loves quail eggs, lives in Paris and is 82 years old.”2 From there, the artist set about attempting to meet Chopin, and in the meantime he began to accumulate a wealth of data and documentation on him. All of the material was gradually distilled into the content of Vonna-Michell’s performances and installations made at different moments of his quest.

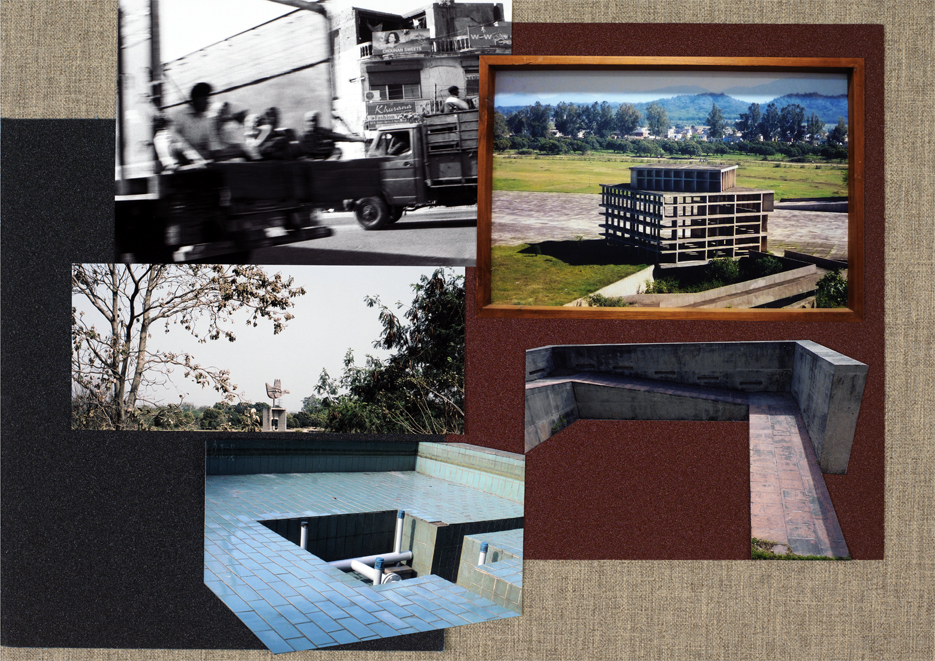

On January 29, 2014 Vonna-Michell gave an artist talk at Université du Québec in Montréal. There, within the twenty-five minutes that he had allotted himself,3 he spoke (among other things) about a series of unexpected encounters made during a visit to Punjab, India. Vonna-Michell used these events as the starting point to write a script set in the city of Chandigarh upon which the work Capitol Complex is loosely based.

The first part of this text introduces the generic character named “Traveller” loitering at the Chandigarh bus terminus “in search of a crevice for a few hours sleep.” “Traveller” then meets with “Waste-picker” gathering the “crackly, brittle plastic called “karak” which is meant to be re-sold. “Traveller” drifts to Sarovar Path and the Rock Garden where two muggers menace him with a knife and steal his bag. At the police station, he hands a report of the incident to “Officer” so that he can get a stamp in order to obtain a temporary passport. “Officer” questions the veracity of “Traveller’s” story (“ you sure you’re not a hippie? No tourists go to the bus terminus, tourists have cars, drivers…”) and sends him in the direction of the Capitol Complex, the seat of government in Chandigarh. Having arrived there, he is allocated ten minutes on the premises, and meanders through many more checkpoints. Then a shift in perception occurs. “Traveller” gradually forgets the purpose of his visit: the Complex disintegrates into minute details, and as the end of the script suggests, his body is all of a sudden displaced: “Furthermore Traveller’s sense of purpose and reason has now become slightly obscured. He doesn’t know how to communicate his reason for wanting access into Capitol Complex, who he needs to find, let alone which edifice is his destination.”4

Since 2012, Vonna-Michell has produced several instantiations of Capitol Complex. The Prelude of the series uses a Telex projector to show a sampling of images, interspersed with pages of the script, with or without a soundtrack. The most elaborate version recently exhibited at VOX image contemporaine (Montréal) is composed of a dual slide projection with two soundtracks playing alternately: in the first, Vonna-Michell is improvising from the script and in the second, another narrator reads excerpts of the text translated in French. The voiceover starts with Act 4, when “Traveller” arrives at the Complex. Other versions of the piece gather photographic prints and pages of the script on panels affixed to a shelf or a table construct. The soundtrack is broadcasted from wall-mounted speakers. For the exhibition at Gallery TPW, Vonna-Michell devised a slanted table construct on which he montaged images and textual fragments from the four acts of the script.5 The table functions both as performance arena and display apparatus. In contrast to the vertical slide projection where one image follows the other, this horizontal plane seems to suggest at first the activity of editing visual material (which Vonna-Michell does to a certain extent when he is narrating photographic prints during a performance). While the story unfolds sequentially in the soundtrack, the simultaneous perception of these objects on the table creates other streams of association.

Vonna-Michell’s preoccupation with the meanings of cultural transfer and appropriation is present in most of the works that take a city as a point of departure.6 However, this particular investigation into what I would describe as a “phenomenology of tourism” started in 2012 while he was artist in residence at the National Trust’s Gibside Property, in Gateshead, UK. During his stay there, he produced Ulterior Vistas (2012) a slide-based installation in which he obliquely commented on the way he had lost his autonomy while he was momentarily embedded in the site as a producer of surplus value for the host institution. While the slide sequence gathered images of picturesque loci, the soundtrack was composed of Vonna-Michell’s spoken word narration mimicking the fractured language of an auctioneer (with bombastic musical accompaniment). While this piece attempts to convey the experience of being trapped in an heritage site, Capitol Complex investigates the discrepancies between the legacy of European modernist architecture in Chandigarh and the daily struggles of its inhabitants that impact upon a constantly shifting post-colonial landscape.

After India’s emancipation from Britain in 1947, the city became a tabula rasa of sorts for which Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru could imagine the modernization of the state. In 1950, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret were invited to partake in this infrastructure project with local urban planners and architects. Le Corbusier conceived the city as an anthropomorphic program with the administrative quarters, the Capitol Complex, acting as the head. Instead of being integrated into the fabric of everyday life, the buildings are physically turned away from the city, and were secluded in a constructed landscape composed of an artificial hill that blocked the real mountains from view.7 In 2012, and for many years, the Complex has been a pilgrimage site for connoisseurs of modernist architecture but access to the site has become heavily restricted as a non tourist zone. The difficulty of taking into account the gap between Le Corbusier’s utopian program for Capitol Complex and its present administered and policed existence asks for a more complex understanding of the “colonial modern.” As Marion Von Osten states, this paradigm “does not focus on the colonial conditions of modernity as based on traditional distinctions between civilized/uncivilized, ruler/powerless, specialist/layman, but rather on the historical conjuncture of modernity and its internal critique.”8 The attempt to escape these easy dichotomies on the level of a research methodology is where the complexity of Vonna-Michell’s investigation into the fabric of Chandigarh lies. No longer defined as the matter of a firm constellation on which to base an exegesis, contextual information bleeds into a chain of signifiers subjected to narrative disintegration and entropy. The script is both a matrix for speech acts and a topological representation of architecture always already displaced. This movement is operative in the “characterization” that makes the various instantiations of the piece, where Vonna-Michell’s voice shifts from the subject position of “Traveller” to that of “Waste-picker”, and the “Officer”, and then to a generic person that becomes displaced.9

In order to better understand the play of space and time within Vonna-Michell’s work, it is necessary to complicate the way in which this voice is more often than not identified with one individual and thus, his proper name. In its recent canonization, performance art casts a unique subject at the epicenter, as the conveyor of meaning (the artist must be present, or at least produce a presence). The value appended to speech is the bearer of this singularity, a signature style. However as Mladen Dolar has stressed, it is impossible to define precisely what it is that we aim to posses by listening to our voice and claiming it as ours.10

When he performs in front of an audience, Vonna-Michell relies on the attention of people to keep balance as if he was walking on a tight rope. Everything is menaced: the thin invisible thread could fall apart and then words would accumulate with nothing in between to keep them together. When the egg timer rings,11 the verbal delivery as well as this moment of transference is final. This cut can be compared to the break of a stream of thoughts at the end of the psychoanalytical session. By delocalizing the voice once more from the body, Vonna-Michell’s installations instantiate what filmmaker and writer Marguerite Duras has called the noise of reception. While commenting on the making of her film India Song (1975), Duras explained how she mixed soundtracks so that the temporal intervals between the utterances of her character’s lines would be either shortened or stretched. The a-synchronicity of the image and the sound were meant to foreground that while talking, these characters spoke against each other (in fact, she broadcast their recorded voices back to them while she was filming the movement of their silent bodies, so that they “turned over”).12 Vonna-Michell’s work is often compared to that of the author W. G. Sebald’s interpolation of photographic images within his written narratives, but, in my opinion, the friction of soundtrack and photographic constellations in real time brings the artist’s approach closer to Duras’s temporal delays, as well as the “recitation” films of Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet13 Far from a nostalgic fixation on scarce technology (the slide projector), the configuration of the audiovisual apparatus used by Vonna-Michel introduces a time lag specific to analogue media in which flickering levels of noise and signal construct representation.

Vonna-Michell once told me about his complicated relationship to the written word – that until Capitol Complex, he never wrote scripts. His texts (improvised or otherwise) are always absorbed into an oral form that is also, paradoxically, a mode of inscription. In 2011, he published a book gathering images from his slide installations, as well as elaborate text fragments.14 In the book’s prelude, he alludes to the series Finding Chopin: “Since receiving the book last month it has been kept in shrink-wrap. Perhaps due to a reluctance to open, to confront and continue with this story, which is in its seventh year of transformation. Over the years the story’s axis steadied, and became feather-light, but remained just as resolute and evasive as when first spoken.”15 When I started thinking about this essay, I wondered how it could formally encompass Vonna-Michell’s preoccupation with the deferral of the trace. I was watching Capitol Complex in his exhibition at VOX image contemporaine16 and because of my bad sight I needed to get closer to the slide projections to discern the details. When near, I began to lose the grasp of the soundtrack. In darkness, I wrote notes on a piece of paper, picking up fragments of voice, watching and listening over and over again. When back home, I discovered that this list blended narrative segments of Capitol Complex as well as other works in the exhibition that I experienced several times. I started the first draft of this essay with transcribed sentences from the document and then hoped that it would lead me to another path. However, these fragments of the soundtrack were the closest I could get to the interval in which the contingency of my perception could exist within the text. At the end of the day, I realized that all of my attempts to escape prescribed formats would not go beyond mimicry, or worse, pastiche of artistic strategy. As an author fulfilling a task (to provide context to the present exhibition), I am already inscribed within an economy of mediation and this essay arrives at the tail end of the discursive thread on Vonna-Michell’s work. I had nevertheless wished to linger in this undecidability of the badly seen, and the badly heard, before starting to use the proper language.

Endnotes 1. See Finding Chopin: Endnotes: 2005-2009 (Paris: Jeu de Paume, 2009). Catalogue for solo exhibition at the Jeu de Paume, October 20 – 17, 2009.↩

2. Elena Filipovic, “Nothing is more dubious than this sentence” Finding Chopin: Endnotes: 2005-2009, 14.↩

3. Bypassing the duration of the artist talk that usually lasts about an hour, Vonna-Michell decided to shorten his delivery, and at the end, he asked the audience to provide some questions as a condition for him to continue talking.↩

4.Excerpt from the unpublished script.↩

5. The artist used a similar display with a table at the gallery T293, Rome in 2013, but this time, a self-enclosed room was constructed, and the soundtrack was broadcasted on headphones.↩

6. Berlin for hahn/huhn, 2003-2012, and Detroit for Auto-Tracking Ongoing Configurations. 2009.↩

7. In his book about Le Corbusier’s work for Chandigarh, historian Vikramaditya Prakash writes about the architect’s “masked personal agenda” while he was in the process of fulfilling his commission. Under the guise of urbanization, he casts the inhabitants of Chandigarh as protagonists of a utopian and technocratic scenario: “Critical to the prophetic purpose of modernism. They are its subjects. There are thus some grounds for understanding why Le Corbusier founded the entire Capitol around them-without any exchange and without them ever having commissioned him to do so. Labeled a “futurist thinker,” Le Corbusier in his own personal world, interpreted his commission as a recognition of his messianic mission.” Vikramaditya Prakash, Chandigarh’s Le Corbusier: The Struggle for Modernity in Postcolonial India (University Of Washington Press, Seattle and London, 2002), 95.↩

8. Marion Von Osten, “Introduction” in Colonial Modern: Aesthetics of the Past, Rebellions for the Future (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2010), 11.↩

9. A sound work soon to be released in the form of a LP explores the officer’s point of view. Tris Vonna-Michell, Capitol Complex / Ulterior Vistas. Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea, and Mount Analogue, Stockholm.↩

10. “To hear oneself speak – or simply to hear oneself – can be seen as an elementary formula of narcissism that is needed to produce the minimal form of a self (…) Inside that narcissism and auto-affective dimension of the voice, however, there is something that threatens to disrupt it: a voice that affect us most intimately, but we cannot master and have no power or control over it” Mladen Dolar, A Voice and Nothing More (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2006), 38, 40.↩

11. Vonna-Michell uses this rudimentary device to calibrate the duration of his performances.↩

12. “The voices of reception, in other words the voices that I mixed, you know how I did it? I did several takes and I just blurred everything … So that they exclude each other …. And it makes noise. It’s the noise of reception. I wanted to do a little more of that kind … like when talking about the burning need to drink tea in the heat … ” Marguerite Duras, La couleur des mots : Entretiens avec Dominique Noguez (Paris: Benoît Jacob, 1984), 88. Our translation from the French.br ↩

13. However, his practice distinguishes itself from its predecessors because it emerged in a post-indexical moment, when there is currently an attempt to apprehend the image and the text by its distribution channels rather than by its relationship to an ontological real. See Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2012).↩

14. Tris Vonna-Michell, Tris Vonna-Michell (Zurich: JRP Ringier, 2011). Behind an identical cover, the seemingly same is presented in two variations that were developed through performative improvisations over earlier text versions, and repositioning of images and inserts. The two variations were pendently constructed; book I began in November 2009 at Halle für Kunst in Lüneburg, in which several chapters, texts and images were printed on a Heidelberg GTO printing press on a daily basis during the exhibition “Capstans”. In 2010 book II began as a revisitation and expansion of the first variation, in which the previous narratives, images and inserts were reconstructed.↩

15. Ibid., n.pag.↩

16. Tris Vonna-Michell, VOX image contemporaine, Montréal, February 7 to April 12, 2014.↩

Vincent Bonin

Vincent Bonin lives and works in Montreal. As a curator, he notably organized Documentary Protocols (1967-1975), a three-part research project (two exhibitions and a publication) dealing with the history of artist-run spaces and parallel galleries in Canada. The exhibitions took place in 2007 and 2008 at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery of Concordia University in Montreal. The accompanying book length publication, under his editorship, was launched in 2010. He is one of the curators (Grant Arnold, Catherine Crewston, Barbara Fischer, Michèle Thériault and Jayne Wark) of Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada (1965-1980), touring nationally and internationally since 2010. He organized with Catherine J. Morris an exhibition devoted to the “conceptual period” of American art critic Lucy R. Lippard entitled Materializing “Six Years”: Lucy R. Lippard and the Emergence of Conceptual Art on view at the Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Ar, Brooklyn Museum in 2012-2013. Recently, he curated D’UN DISCOURS QUI NE SERAIT PAS DU SEMBLANT / ACTORS, NETWORKS, THEORIES addressing the way the way in which a body of theoretical texts by French philosophers was assimilated in Anglophone art milieus from the late 1970s to the present. The first part took place at the Leonard and Bina Ellen Gallery in 2013, and the second part is slated to open in september 2014 at Dazibao, Montreal. His writings have been published as chapters in such anthologies as Ouvrir le document: Enjeux et pratiques de la documentation dans les arts visuels contemporains (Les presses du réel, Dijon, 2010), and Institutions by Artists (Fillip, Vancouver, 2012).

Tris Vonna-Michell

Tris Vonna-Michell (UK/Sweden) stages installations and performs narrative structures, using spoken word, sound compositions and photography. His works extend over several years as context-specific iterations, which develop with each exhibition, acknowledging how the perception of historical material is affected by the conditions of the present.

Tris Vonna-Michell (1982, Rochford, UK) is based in Stockholm, but currently in residence at the Darling Foundry in Montreal. He studied at the Glasgow School of Art as well as the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. His work has recently been featured in several international institutions including VOX, Montreal, Centre George Pompidou, Paris (2014); MUSAC in León, Secession, Vienna and Mudam, Luxembourg (2013); the 9th Shanghai Biennale, the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2012); WIELS, Centre d’art contemporain, Brussels, the Hayward Gallery, London and the CCA, Glasgow (2011). His works are in the permanent collections of the Tate Modern, London, the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and Centre national des arts plastiques, Paris, among other institutions. He is represented by Jan Mot in Brussels and Mexico City, Metro Pictures in New York City, T293 in Rome and Overduin and Kite in Los Angeles. Vonna-Michell is shortlisted for the 2014 Turner Prize.