Cape Town-based writer Sean O’Toole responds to Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s To Photograph The Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light at Gallery TPW and across Canada.

For much of the past two decades, the work of the London-based photographic duo Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin has, in varying ways, challenged the orthodoxies, traditions and stabilities of photojournalistic practices. Uncomfortable with the “dubious relationship between photography and reality,” as they put it in 2008, they have placed deliberation and reflexivity at the centre of their increasingly conceptual practice. While centrally bound to the idea of photography, their practice has gradually become more multi-faceted: it now encompasses not only the action of making a photograph, but also the related activities of collecting, archiving, disassembling and re-contextualizing photographs—sometimes their own, but also those made by other photographers. Their most recent project, To Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light, showcases the workings of this many-sided practice, and includes their own photography alongside the work of anonymous photographers contracted by Kodak.

The title of their project quotes a euphemistic expression used by Kodak executives to describe the ability of their new colour film stocks to better represent a wider range of skin tones. For many years, the chemistry of Kodak’s colour films exhibited a light-skin bias. Early on, in the 1950s, this was already a point of complaint among users, notably photographers producing mixed-race group portraits for school graduation and class photos. “The picture results showed details on the white children’s faces, but erased the contours and particularities of the faces of children with darker skin, except for the whites of their eyes and teeth,” explains Lorna Roth, a communications scholar at Concordia University. Roth’s 2009 study of the early technical limitations of Kodak film directly informed Broomberg and Chanarin’s project, delivering its idiosyncratic title and clarifying the broad sweep of filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard’s 1979 statement that Kodak film was “racist.”

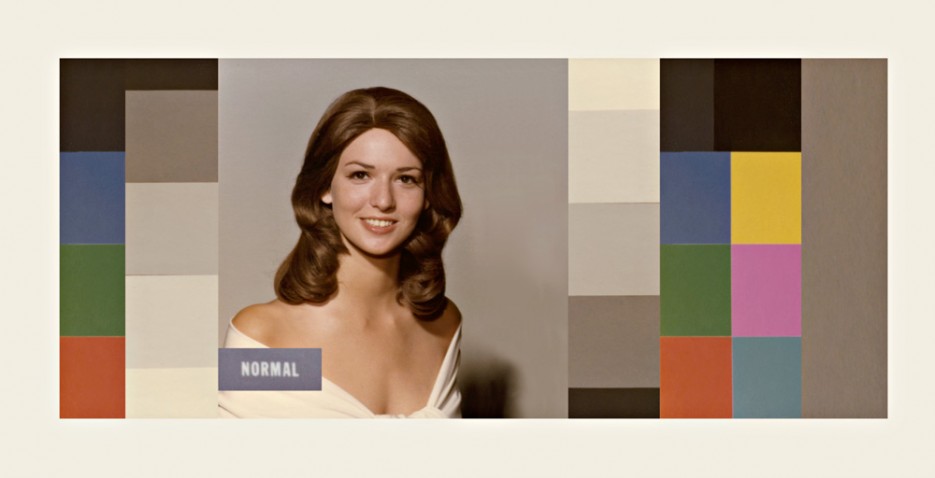

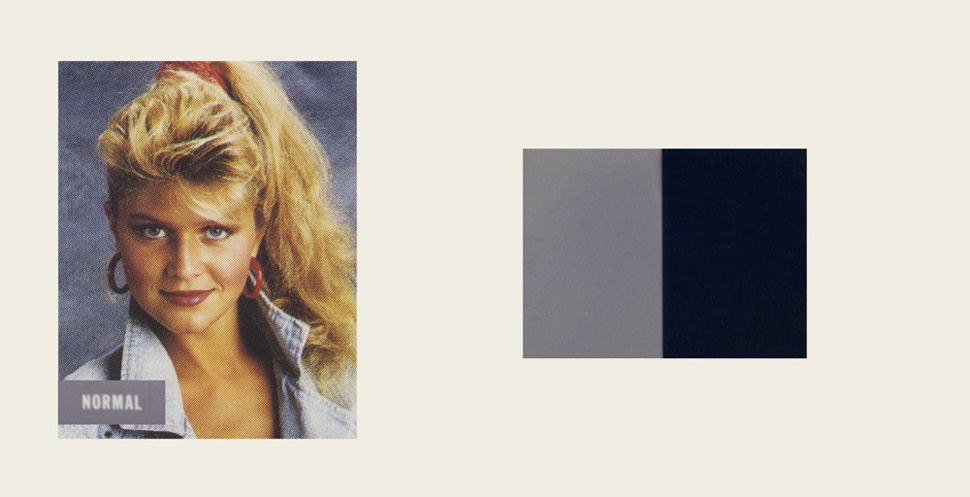

The chemistry of Kodak’s early film was indeed just that. “At the time film emulsions were developing, the target consumer market would have been ‘Caucasians’ in a segregated political scene,” says Roth. “Their skin tones would have been less likely to be the basis for thinking about dynamic range, because most subjects in a photograph would either have been all light-skinned or all darker-skinned.” This invisible science was visually buttressed by Kodak’s early, racially biased colour-balancing reference cards. Introduced in the 1940s as an aid for laboratory technicians measuring and calibrating skin tones, these test cards (or plotting sheets) featured a white model wearing a colourful, high-contrast dress. Further defining hallmarks of these cards, which are now collectible and traded online, was an abstract colour grid and verbal caption stating the film type together with the word “normal.”

Colloquially known as “Shirley” cards, after the name of the first model, these reference cards manifested a normative skin-tone bias that was already inherent in the chemistry of the film itself. As part of their contribution to the CONTACT Photography festival, Broomberg and Chanarin have adapted six of these early “Shirley” reference cards for display as outdoor billboards. They have minimally altered the appearance of the original cards, removing only the reference to Kodak. The billboards retain the original portrait, normative verbal captioning and abstract colour grids, the scale of which has been slightly expanded. This subtle intervention gestures toward a distinctive seam in Broomberg and Chanarin’s recent practice: their interest in the way graphic symbols and abstract markings interfere with the reading of photographs, especially portraits.

In an earlier, expanded version of To Photograph the Details… shown in London in 2012, the photographers presented a grid installation of a series of test portraits depicting similarly framed sitters, their identities variously obscured by circular, triangular and square-shaped graphic devices. These test portraits, whose formulation was determined by notebooks and experiments found in an amateur studio bequeathed to the photographers, share certain visual affinities with their 2011 project, People in Trouble Laughing Pushed to the Ground, a large-scale enquiry into the graphic markings that appear on some of the 14,000 black-and-white contact sheets in the Belfast Exposed Archive. These user markings share some of the violence implicit in the discarded Rwandan identity photographs appearing in their book Fig.

Published in 2007, Fig. marked a decisive move away from their earlier issue-oriented photojournalistic style, toward a practice characterized by visual non sequiturs and apparent randomness. To Photograph the Details… perpetuates this trajectory. The project includes a tightly framed study of a palm frond bathed in purple and pink hues. The single photograph, which yields very little visible information, is the outcome of an experiment that, depending on how you view it, possibly went horribly awry. In 2012, Broomberg and Chanarin travelled to Gabon in West Africa on an assignment to photograph initiation rituals associated with Bwiti, a syncretic religion that originated among the Fang people. They restricted themselves to using only expired late-1950s Kodak film stock for the assignment. Back in London, they managed to salvage just one frame during processing. This lone image, which shares the same minimal aesthetic as their studies of commercial photography studios across the United States for the project American Landscapes (2009), begs a simple question: Did they really go to Gabon? If yes, why exhibit this failure?

The intellectual lineage of To Photograph the Details… can be traced back to a photograph Broomberg and Chanarin made in 2004. To mark the 10th anniversary of South Africa’s democracy, the pair returned to the country of their youth to work on a book project. Then, still working in an explicitly documentary mode, their narrative of change and stasis in South Africa included a portrait of an elderly man with short-cropped, greying hair and stretched earlobes—the latter feature attributable to his missing Isiqhaza, the decorative ear adornments worn by Zulu people. A detailed caption note clarified the significance of the portrait. A resident of Alexandria, a crowded township in northern Johannesburg, Mr. Mkhize had only been photographed twice before meeting the photographers: first for his Pass Book, an identification document used by the apartheid government to control and regulate the movements of black South Africans; and again for his Identity Book, a document that enabled him to participate in the country’s first non-racial elections in 1994.

Redolent of the formal portrait style Broomberg and Chanarin perfected while working at Colors, a reportage magazine based in Italy, Mr. Mkhize’s portrait is also conceptually linked to a more recent investigation, The Polaroid Revolutionary Workers, a project similarly engaged with the materiality of image production. According to historian Eric J. Morgan, in October 1970, Ken Williams, an African-American photographer and Polaroid employee, stumbled upon a sample identification badge for the South African Department of Mines in Polaroid’s headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Further investigations by Williams revealed that Polaroid was selling its patented ID-2 camera system—which could make identification cards nearly instantaneously and included a boost button designed to increase the flash when photographing subjects with dark skin—to a South African distributor, Frank and Hirsch. Polaroid’s system was especially popular with state agencies involved in population classification, notably the Bureau of Mines.

Unsatisfied by the responses to his initial enquiries about the ethics of doing business in South Africa, Williams founded the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers’ Movement with two colleagues. This anti-apartheid lobby group attracted considerable public interest, eventually prompting Polaroid to dispatch a fact-finding mission to South Africa. Despite encountering indisputable evidence of the humiliation their product was linked to, Polaroid opted to continue doing business in South Africa while imposing strict conditions related to wages and employment equity on its distributor. In 1971, as an “experiment” in ethical business, Polaroid imposed a ban on the sale of its products to the apartheid state and its bureaucracies. News reports in 1977 revealed that its distributor was flouting the ban by supplying the state through a front company. Polaroid promptly disinvested in South Africa.

Broomberg and Chanarin obliquely included this history in a recent exhibition in Johannesburg, showing a series of mostly blurry, close-cropped, split-frame Polaroid images of South African flora. The images were made on a road trip, using an ID-2 camera. One key selling feature of this camera was its ability to record frontal and profile views of portrait subjects on a single sheet of film. Broomberg and Chanarin’s photographs declared none of this history. A similar strategy of open-endedness and incompletion typifies the display of their “Shirley” billboards. Why the subtlety, if not outright refusal? Why this reliance on off-image text to determine a reading of their images and intentions? One argument might maintain that a photograph is incapable of holding this sort of information, that the material of their enquiry is latent while photography trades in the visible. It is an inadequate argument for Broomberg and Chanarin.

In early 2008, they were invited to participate as jury members for the World Press Photo Awards, photojournalism’s top prize. It was, they wrote in a controversial editorial published shortly after the winners were announced, “a good opportunity to gauge the vital signs of a photographic genre in crisis.” Their editorial, which summoned the dissenting voices of Susan Sontag and Bertolt Brecht—whose 1955 publication War Primer is the source of a “belated sequel” book of conflict images compiled by Broomberg and Chanarin and published in 2011—included commentary on the award process’ blithe dismissal of caption information. Photographs that relied on captions, they wrote, were largely rendered “impotent.” In a detailed discussion of an image that caught their attention during the judging, they additionally noted, “It is precisely the image’s ambiguity, its reliance on its caption, that makes it so much more interesting.”

In their editorial, they also considered the surplus production of images in an age saturated with abundant and perfectly legible documents of initiation rituals in Gabon and degradations from the battlefield. “Does the photographic image even have a role to play any more?” they asked. Their subsequent practice has suggested this answer: “Yes, but.” Yes, because photographers cannot avoid making images. It is the sine qua non of what they do. But—and here the conjunction modifies the affirmative—this permission has to be matched by an evaluative criticality. Referring to another submission that intrigued them—a photograph of a hand-painted shooting target depicting a lush, green landscape made by an occupying soldier and placed in the arid Afghanistan landscape—they argued for the rehabilitation of the role of photojournalists “from an event-gathering machine into something slightly more intelligent, more reflective and more analytical about our world, the world of images and the place where these two worlds collide.”

An angry riposte to the throttling iconophilia that defines the reading and appreciation of photography, their statement also challenged the hoary notion that criticism is a kind of disinterested spectatorship. Criticism is also embodied in a creative act. There are a number of precedents for this within the history of mechanical image-making. In 1968, Japanese photographers Takuma Nakahira and Koji Taki published the first edition of Provoke, an experimental magazine that functioned as a showcase for a group of avant-garde photographers, including Daido Moriyama. The magazine’s grainy, often blurred and radically cropped photographs interfered with the assumed basic function of photographic representation, verisimilitude. This destabilizing ploy aimed to highlight a fundamental deficiency in the kind of photography then widely in circulation in Japan. “The image by itself is not a thought,” declared the authors of a jointly written manifesto appearing in the first edition of Provoke. “It cannot possess a wholeness like that of a concept.”

The shift from “image” to “concept” was a decisive gesture within 20th-century art practice. Its ramifications are, however, still being explored in photography. In making sense of Broomberg and Chanarin’s increasingly argumentative and dialectical practice, one cannot overlook the actions and utterances of Martha Rosler, Chris Marker, Allan Sekula or Walid Raad. Their work variously and differently foreshadows Broomberg and Chanarin’s increasing retreat from the liberal humanist tradition that underpins photojournalistic and documentary practices. But I want to return to Godard, whose statement about Kodak, uttered after his inconclusive return visits to Mozambique in 1977 and 1978, gave impetus to the making, collecting and retrofitting of the images gathered under the rubric of To Photograph the Details….

In a 1962 interview with Cahiers du Cinema, Godard spoke of the continuity between his earlier practice as a critic at the magazine and his then relatively new role as a filmmaker. “Today,” he offered, “I still think of myself as a critic, and in a sense I am, more than ever before. Instead of writing criticism, I make a film, but the central dimension is subsumed.” Godard believed that there was “a clear continuity” between all forms of expressions. “It’s all one,” he stated. In the case of Broomberg and Chanarin, this stratagem of explicitly folding criticism into the creative act has become increasingly central to their practice since the 2007 publication of Fig. Unlike Duchamp, who subordinated looking to thinking, Broomberg and Chanarin’s aim is to establish parity between active looking and committed reading. Their strategy is not without risk, as Godard’s later engagé cinema revealed. But, at this midpoint in their career, it represents a necessary compromise between outright refusal and a critical practice dedicated to showing something.