170 St. Helens Ave. Toronto, ON, M6H4A1

416.645.1066 | info@gallerytpw.ca

Hours: Tues to Sat, 12pm - 5pm

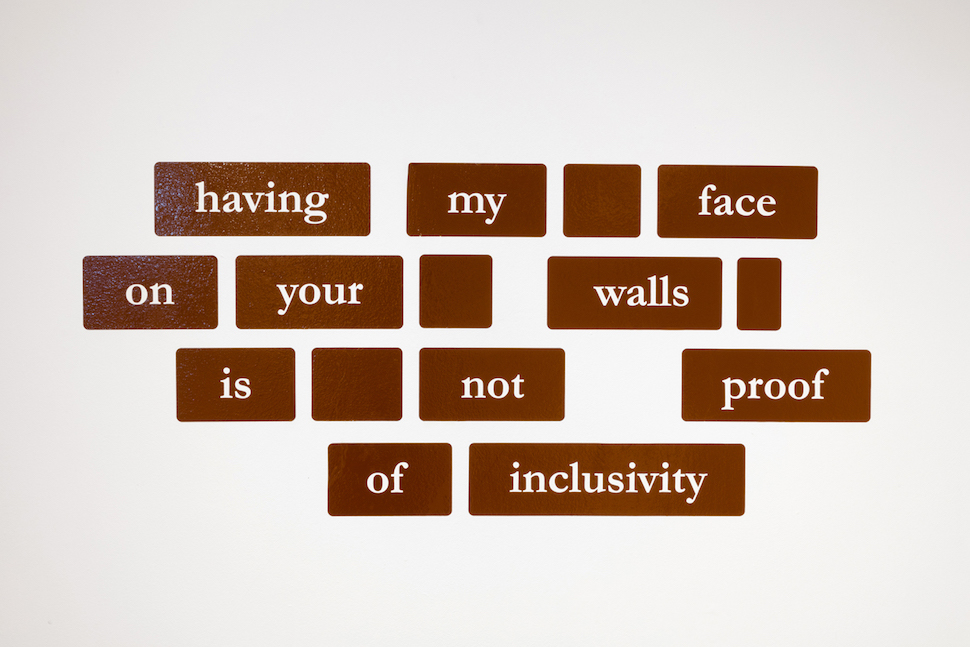

As someone who has worked in artist-run culture in various capacities, I am fascinated by the vast contrast in the way people are valued when entering an

institution as an artist or as a staff member. The artist is generally brought in as an external expert, tasked with changing the face of the institution on a temporary

basis. They are often given autonomy, but with the understanding that it is for a very short time only. The worker, however, is tasked with understanding their

place within the established system or hierarchy, and doing only what is asked of them. There is usually little room for independent thought, let alone action. The

lack of trust, independence, and respect that I have felt while working as a staff member in various arts institutions, is ultimately what made me decide that it was

not a viable career path for me in the long term, and instead I decided to focus on my art practice.

170 St Helens Ave Toronto, ON M6H 4A1 | VISIT | T: 416.645.1066 | info@gallerytpw.ca | HOURS: Tues to Sat, 12pm - 5pm

170 St Helens Ave Toronto, ON M6H 4A1 | VISIT

T: 416.645.1066 | info@gallerytpw.ca

HOURS: Tues to Sat, 12pm - 5pm

T: 416.645.1066 | info@gallerytpw.ca

HOURS: Tues to Sat, 12pm - 5pm