No Looking After the Internet is a monthly “looking group” that invites participants to look at a photograph (or series of photographs) they are unfamiliar with, and “read” the image out-loud together. Chosen in relation to an exhibition, an artist’s body of work, or an ongoing research project, the looking group will focus on difficult images that present a challenge to practices of looking. If these images ask the viewer to occupy the position of the witness, No Looking offers the space and time to look at these photographs in detail: to return to these difficult scenes in another context where we can look at them slowly and unpack our responses to the image.

Premised on the idea that we don’t always trust our interpretive abilities as viewers, the aim of No Looking is to examine the differences between witnessing and looking. How does a slower form of looking allow us to be self-reflexive about our role as spectators? How do we look at these images differently when we interpret them with a community of others?

No Looking takes its inspiration and name from No Reading After the Internet, an out-loud reading and discussion group facilitated by cheyanne turions and Alexander Muir that meets regularly in Toronto and Vancouver (http://noreadingaftertheinternet.wordpress.com/).

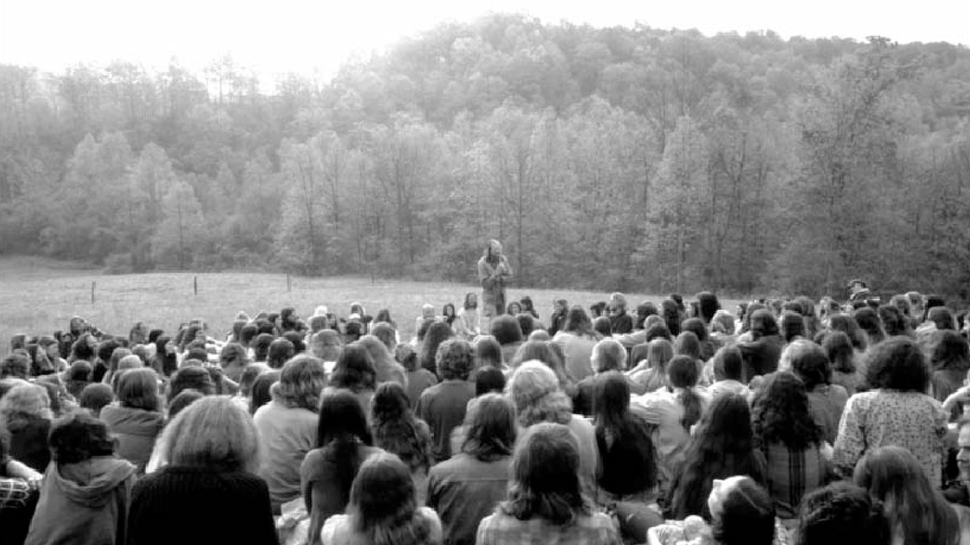

Jason Lazarus’s Too Hard to Keep

co-facilitated with Michèle Pearson Clarke

Tuesday, July 30, 2013, 7:30 pm

TPW R&D

(1256 Dundas St. W.)

The July meeting of No Looking turns its attention to Jason Lazarus’s Too Hard to Keep project (2010–ongoing), a growing archive of vernacular photographs donated by owners that find the images too hard to hold onto, but too meaningful to destroy. Focusing on the site-specific installation of the archive currently on view at Gallery TPW, this month’s looking group will consider the tensions at play in the premise of the project, which troubles the boundaries between the private and public viewing context for personal photographs. What does it mean to refuse to look at a photograph you own, but to insist that others see it, in public? And how might Lazarus’s installation strategies—which suggest thematic connections between some of the archive’s thousands of images—influence our interpretations of these photographs and our projections about their lives as images before they entered the space of the gallery?