In response to the first three meetings of No Looking After the Internet, part of the “Coming to Encounter” curatorial residency at Gallery TPW R&D, writer Alison Cooley reflects on the ways that curatorial decision-making, artistic authorship and the group’s shifting social dynamics shape the practice of collective looking.

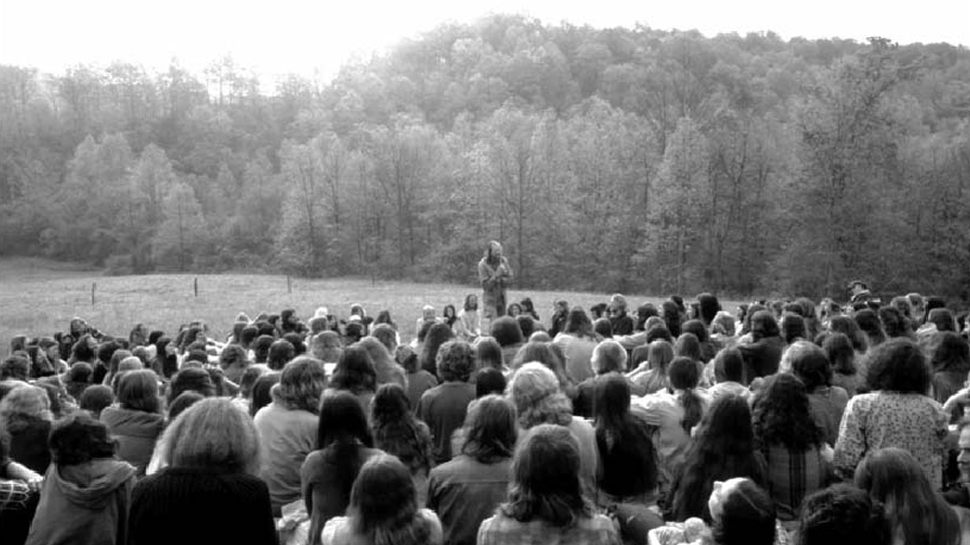

—-At the beginning of each session of No Looking After the Internet, Gabby Moser sets out the guiding ideas and expectations for the group. No Looking borrows its format from the collaborative reading group No Reading After the Internet and stages monthly meetings where the informal group looks at and thinks through responses to difficult images. At the outset of the series, Moser introduced the concept of slow looking, which she described as a kind of socially mediated, perhaps naïve, coming-to-terms with the image through the practice of reading it communally: describing it formally, and collaboratively processing its significance. No Looking asks how we can respond appropriately to images of violence, trauma, or injustice in a group setting, inviting us to recognize our inexpertness and complicity, and suggesting we can move beyond simply bearing witness to difficult images.

Throughout the first three sessions, a shifting group of participants examined a number of differently-difficult images, taking the opportunity to think through both the politics of the image and of the social space in which our discussion took place. Discussions have been by turns halting, enthusiastic, tender, and confrontational. The group dynamics have continually changed between participants, mediated by voices of curatorial and artistic authority. As each meeting has examined a particular set of images related to a concurrent exhibition or project, each encounter with the image has also become an encounter with a curatorial or artistic vision for that image. In our attempts to address and thoughtfully read the images, curatorial hints have been both valuable and impeding, always at risk of distracting us from the task of understanding the space we occupy in relation to the image, and instead giving away factual or historical information, emphasizing curatorial decision-making, or privileging the artist or curator’s set of conjectures.

The first No Looking meeting coincided with Deanna Bowen’s exhibition, Invisible Empires, at the Art Gallery of York University. For the discussion, Bowen and Moser introduced two postcard images of the 1911 lynching of Laura Nelson and her son (whose first name was unknown to us) in Oklahoma, and the crowd of onlookers who had assembled around their bodies to pose for the photograph. Both Bowen and Moser visibly struggled with how much information to provide to viewers, but the general lack of archival information surrounding the photographs left room for productive and disturbing gaps, even in their knowledge. In stark contrast to the strategic absence of the black victimized body in Bowen’s exhibition, the photographs revealed material evidence of the violence of racism, and suggested its currency and circulation through the postcard format.

Our discussion of the Nelson lynching photographs began with formal observations and reactions to the difficulties of the images, and quickly felt frenzied and helpless: as if making these tiny discoveries or pressing the artist and curator for historical details was a way to effectively come to terms with the ugliness of the photographs and what they represented. Self-reflexivity about our communal looking practices became key, and one participant directed our attention to the fact that the photograph of the crowd dominated our discussion, while we shied away from addressing the (arguably more gruesome) image of the Nelson bodies alone. Bowen’s presence was integral to the discussion, and she effectively questioned the viewers’ tendency to seek answers from her as an artist, and to absolve feelings of guilt and shame through looking and reacting in horror.

At its next meeting, the group took as its subject sets of cards available at the HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN WRONGS exhibition at the Ryerson Image Centre (RIC), which reproduced in a small, hand-held format a selection of images from the show. During the discussion, artistic and curatorial authority again became a point of interest and contention. While the images we discussed had both clear authorship and ownership as part of the Black Star Collection, the information that accompanied them was minimal. Captions provided some context (attributing a photographer, date, and location to the photograph), and the back of each card included a list of global human-rights events that occurred that same year.

Our first two discussions were dominated by images that are, or were, intensely public—circulating in a particular economy of viewership—, wherein money has been exchanged for the impact, violence, or memorial quality of the photograph. As photojournalism, each of the Black Star images, despite their re-contextualization in the RIC exhibition, presented insight into a global market for consuming images. The photo cards presented an interesting comparison to the lynching photographs in that each circulated commercially, albeit in different contexts. Our group did not ever get to discuss the complex ethical distinction between consuming a photograph of violence or war in a newspaper or a magazine, and purchasing a photograph of a lynching, however, because considering the images in the context of the exhibition at the RIC dominated our discussion.

The participants affiliated with RIC (curatorial and administrative staff who attended that meeting of the looking group) were quick to give answers and offer opinions, and to provide what was often interesting (if unsolicited) information (for example, which cards visitors had chosen to take most frequently). This felt stultifying in the context of our own exploration and coming-to-terms with the images. Often the RIC-directed discussion centred around the show and Mark Sealy’s curatorial decisions, rather than the problem of the images in front of us, and their format as cards. To the RIC staff, these two things were perhaps indistinct, and they felt moved to share their own experiences of the show and its process. But for other participants, the question of what these images meant in this smaller, tangible context, was overshadowed by the curatorial discussion.

Ideally, looking group participants should share the responsibility for misdirecting discussion, asking questions of the artists and curators, and trying to acquire background information about the images. We often hurt ourselves and the discussion by doing this, because we seek information that simply does not exist, or draw connections we cannot justify in order to supplement our inadequate knowledge of the image. In our democratically formatted discussion, viewers and participants also bear the burden of directing discussion and not allowing either the curator’s voice or our fascination with the factual to dominate. In No Looking After the Internet, it becomes our prerogative as viewers to kill or valorize the curatorial.

At the third meeting, artist Chris Curreri shared a set of photographs found in a junk store, mostly self-portraits of a lone German woman. The images, reminiscent of contemporary, smartphone-era “selfies” appeared to document a troubling and sudden deterioration in her health. The difficulty and necessity of coming to terms with the indeterminacies of anonymous images again came into conflict with our impulse to analyze, to ask, and to understand. One participant suggested that our attempts to deduce all the factual information about the photographs was honourable—that our obsession with the past and our desire to infer the terms of the past are “what we call history, and some of us do it for a living.” Another mentioned, in reference to the subject’s indeterminate illness (manifested through a sudden pallor and weight loss in the later images), that we could not assume it was cancer, and rather that we must live with the uncertainty of the image and refrain from over-championing our guesses, however educated they may be.

An unexamined thread from the HUMAN RIGHTS HUMAN WRONGS exhibition was picked up in the discussion of Curreri’s found photographs—the central problem of what to do with images that are hard to look at, but also hard to dispose of, to forget. Why do we want to keep them? Curreri’s responses were appropriately indecisive, and many participants felt moved to reflect on what their reactions to finding these images would have been.

Of the groups of No Looking images thus far, Curreri’s found photographs presented the most satisfyingly dissatisfying answer to our perpetual tendency to ask the artist. In this case, I found the artist’s helplessness worked effectively against the audience’s questions. He did not have any set of privileged knowledge to confer onto the viewers, only a more intimate or personal connection to the images.

In many ways, Curreri’s images seemed least difficult, both because they represented the amateur photographic attempts of a woman to whom we had no connection, and because they did not appear to provide evidence of any cruel or systemic violence. While many of the participants agreed that there was something troubling about these images, perhaps my ease with the discussion and with looking at Curreri’s found photos (at each previous discussion, I felt compelled to look away from the images), meant they were simply not as deeply unsettling as the others. Perhaps we inscribe these images as “difficult” by bringing them to this discussion, and I wonder if this is an appropriate strategy. Moser pointedly asked if we could consider these images difficult, to which some participants simply reframed the question to emphasize subjectivity: “difficult for whom?”

One recurring element of No Looking is the tricky social dynamic that operates in the discussion; the tendency for people to want to respond and to jump in. In a room full of artists and scholars and people interested in social justice, the aim often appears to be to figure out the answer, to get to the bottom of the image’s meaning, to reveal information others may have accidentally overlooked. Are we really looking slowly and carefully in this context?

In a solitary practice of looking, we often have a tendency to make small discoveries in the image, feel some thrill and excitement, some gasp of scholarly opportunism. In a situation like No Looking, I’d suggest we need to be careful about those moments, and to balance a sensitivity to the image and its context (known or unknown), and a sensitivity to the group, with a desire to emphasize one’s own discovery.

No Looking is an exercise which necessitates the viewer’s vulnerability, awkwardness, and care. We don’t always achieve those things, as the social tensions always present in this group of divergently-thinking and divergently-privileged individuals underscores. When we look alone, we may not feel the need to account for our actual practices of witnessing, only for the things we eventually say publically about the image. But when we look together (or refuse to look, together), we can become accountable for both our individualistic discovering practices and our tendency toward groupthink. I’m not sure the value in No Looking After the Internet is that it makes looking at difficult images any easier, or proposes an alternative. Instead, its value is in its ability to prompt us to think through the social dynamics of looking and witnessing.